When the Supreme Court quietly cleared the way for Texas to use its new congressional map in the 2026 midterms, it did more than settle a technical dispute between judges. It chose, in a high-stakes moment, to prioritize stability and timing over serious allegations that the map was engineered to dilute the power of voters of color. The justices did not bless the map as fair or constitutional. They simply decided that, for at least one more election cycle, Texas Republicans and President Donald Trump will get the lines they drew.

At the heart of the fight is a stark conflict between a lower court’s warning and the Supreme Court’s caution. A three‑judge federal panel had concluded that Texas’s 2025 map was likely unconstitutional racial gerrymandering and ordered the state to revert to its 2021 lines. That ruling would have scrambled candidate plans, fundraising, and outreach just as the 2026 cycle was gearing up. The Supreme Court stepped in and hit pause: it blocked the lower court’s order, allowing the new lines to stay in place while appeals unfold. On paper, the move is “procedural.” In practice, it decides which voters count where in the next national election.

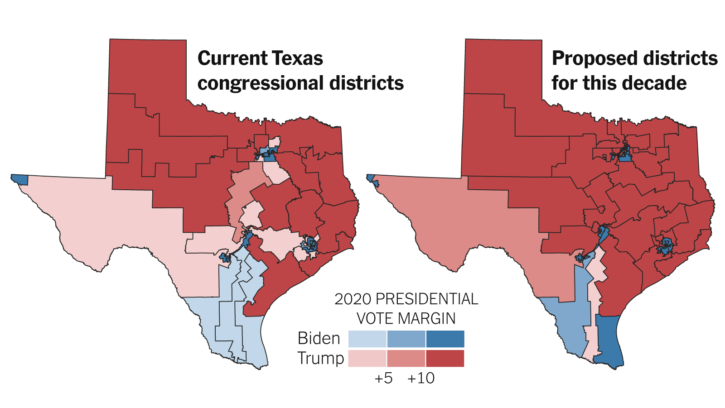

The map itself reflects a clear strategic project. Drawn at Trump’s urging, the new districts convert several previously competitive or Democratic‑leaning seats into reliable Republican strongholds. Analysts estimate that the plan could net the GOP roughly five additional House seats, giving Republicans control of about 30 of Texas’s 38 districts. In a narrowly divided House, that edge is enormous. Texas alone becomes a bulwark against a Democratic comeback, turning what might have been toss‑ups into comfortable Republican insurance policies.

That is why the decision resonates far beyond Austin or Washington. For Republicans, it is a model of how to entrench power through cartography rather than persuasion. If district lines can be locked in for at least one election—even when a lower court thinks they likely violate the Constitution—the immediate political payoff is obvious. For Democrats and civil rights advocates, the ruling looks like confirmation that, on the terrain of redistricting, legal victories often come too late to matter for the election already in motion.

Crucially, the Court’s majority anchored its order in timing rather than in a full endorsement of the map. The conservatives emphasized that the lower court acted too close to candidate filing and primary dates, invoking the now‑familiar idea that federal courts should be wary of “last‑minute” changes to election rules. Over the last decade, that instinct has hardened into a pattern: when a dispute lands at the Court’s door in the shadow of an election, the justices are far more likely to preserve the status quo—even if that status quo is a law or map under serious constitutional cloud.

The Texas order fits squarely in that pattern. It is brief, unsigned, and pointedly narrow. The document does not say whether the map violates the Fourteenth Amendment or the Voting Rights Act. It does not parse demographic data or weigh expert testimony about how districts were drawn. Instead, it answers a single, immediate question: which set of lines will be used in 2026 while the case continues? The answer—“the new ones”—is all that campaigns, parties, and voters need to know for now.

Yet the dissent from the Court’s three liberal justices underscores what that narrowness leaves out. In their view, letting the map stand effectively locks in race‑based sorting of Texas voters for an entire election cycle, even if the Court later agrees it is unlawful. Redistricting cases are uniquely sensitive to time because once an election has been run on an invalid map, the representational harm cannot truly be undone. No subsequent opinion can retroactively restore voting power that was strategically scattered or packed to weaken a community’s voice.

Those competing instincts—judicial restraint near elections versus the urgent need to stop discriminatory maps before they take effect—define the stakes of the Texas case. The Court chose restraint, and in doing so it sent a message to other state legislatures. Aggressive gerrymanders, particularly those that favor the party aligned with the Court’s majority, may well survive at least one full election cycle if challenges arise late in the calendar. That possibility alone can encourage lawmakers to push boundaries, betting that even a “temporary” victory is worth years of policy influence from a more secure congressional delegation.

For Texans on the ground, the decision translates into something simpler and more personal. Voters in fast‑growing, diverse suburbs will head to the polls in 2026 under lines that were designed to blunt their collective impact. Communities of color that expected the decade’s explosive growth to translate into new representation will instead see many of their members drawn into districts where their ballots carry less weight. They will be told that the courts are still thinking about whether that is lawful—but that, in the meantime, the election must go on.

Nationally, the ruling sharpens the contrast between the theory and practice of American democracy. On paper, the system rests on one person, one vote and a shared commitment to equal political representation. In practice, it increasingly depends on who controls the mapmaking pen and how willing the courts are to intervene when that pen traces districts along lines of race and party. The Supreme Court’s Texas order does not close the book on that debate. It does, however, write the next chapter: in 2026, Republicans will contest the fight for the House on a battlefield they helped draw, and millions of Texans will live with the consequences long after the votes are counted.

Stanley Johnson is an contributing editor for Brothamagazine.com