The line separating hate speech from political speech is one of the most vexing issues of modern democracies. Both phenomena deal with the power of language in society, but they operate in extremely distinct ways and raise distinct questions about freedom, accountability, and harm. For societies dedicated to both human dignity and free expression, it is essential to separate where political speech ends and hate speech begins.

Political Speech: The Lifeblood of Democracy

Political speech is the language of government, policy, and public discourse. It includes arguments about leadership, laws, taxation, foreign policy, and countless other matters that shape public life. On its most fundamental level, political speech is an exercise of the fundamental democratic right to endorse or criticize ideas and candidates. It is the means through which citizens contribute to collective decisions nonviolently.

This type of speech is widely considered the most protected type of speech in democracies. Courts in the United States, Germany, Canada, and India all recognize that without political speech, self-government means nothing. Condemning government corruption, calling for constitutional reform, or defending minority rights are a few examples of political expression. Even highly contentious political views—such as advocating socialism in a capitalist country, or more stringent immigration restrictions in a liberal one—are political speech if they target issues and policies rather than individuals’ identities.

The broad protection of political speech is not designed to ensure harmony but to preserve democracy itself. Societies value that political disagreement is inevitable, and sometimes conflictual, but it is in allowing that contestation that freedom flourishes.

Hate Speech: The Limits of Harm

Hate speech is another set of issues entirely. Rather than arguing a point about governance or law, it assaults individuals or entire groups on the grounds of race, religion, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or disability. Its primary intention is not to persuade but to degrade. Political speech may offend by challenging passionately held views, but hate speech seeks to deny the equal humanity of others.

As an example, calling for higher corporate taxes is political speech; calling for the removal or mistreatment of people on the basis of their race tips over into hate speech. Criticism of the teachings of a religion is the realm of political and cultural debate; stating that its adherents are subhuman or do not deserve rights crosses firmly into the territory of hate.

The consequences of hate speech go further than offended feelings. Hate speech can normalize prejudice, intensify social polarization, and even instigate violence. Hate speech has preceded mass violence in history, from the Holocaust to genocide in Rwanda. Because of this violent potential, most democracies do restrict hate speech despite safeguarding robust political discourse.

Legal and Cultural Differences

The difference between political speech and hate speech is regularly debated in legislatures and courts. In the U.S., the First Amendment offers broad protection, and it is very difficult for the government to censor speech, even hate speech. The present legal test forbids only speech that clearly encourages immediate violence. Thus, much that elsewhere would be considered hate speech is legally protected in the United States.

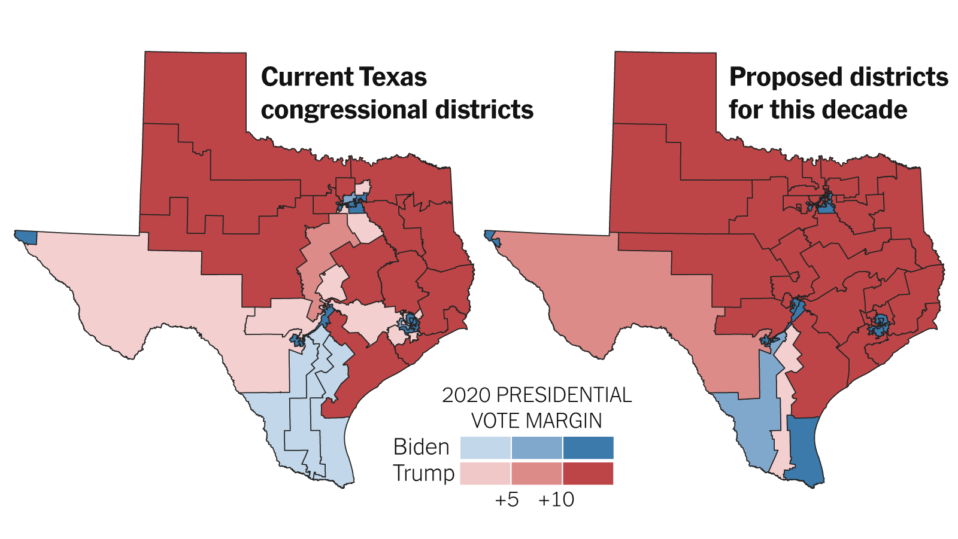

On the other hand, countries such as Germany, Canada, and the United Kingdom sanction hate speech under more limited terms. Germany, because of its Nazi history, forbids Holocaust denial and racist propaganda. Canada criminalizes speech that is likely to promote hatred against identifiable groups. These countries consider limits on hate speech as not censorship of speech but as integral to safeguarding the democratic rights of vulnerable minorities.

Cultural differences also influence where the boundary is set. A culture emphasizing individual autonomy will lean toward near boundless free expression, while cultures that prioritize collective equality will more easily limit speech that endangers social cohesion. In practice, the line between hate and political speech often involves nuanced distinctions that depend on context, history, and intent.

The Overlap and the Gray Zone

The challenge arises where hate speech and political debate intersect. Debate on immigration, affirmative action, or religious freedom, for example, can muddy the lines. A politician calling for increased immigration restrictions is engaging in political debate. But when that rhetoric shifts to labeling immigrants as criminals or parasites, it can amount to hate speech. Similarly, criticizing the policies of a foreign government is political speech, but vilifying people of that nationality crosses the line into targeted hostility.

Intent, audience, and effect all help to determine where speech lands. Speech meant to discuss policy—even heatedly—remains political. Speech that humiliates groups to the point of exclusion or violence crosses the line into hate speech.

Why the Distinction Matters

Being aware of the difference between hate and political speech is not only necessary for legislators and judges, but also for citizens. Democracies require vigorous debate, but they also require respect for each other and protection of the rights of minorities. Hate propaganda, when disguised as politics, threatens the very democratic principles free speech is meant to protect. Conversely, when governments too easily invoke political disagreement as hate speech, they can stifle legitimate debate and harm democracy.

Achieving this balance requires constant vigilance. Its resolution is rarely found in draconian regulations but in ongoing public debate, judicial clarification, and civic education. When societies are able to distinguish between political speech and hate speech, they not only preserve freedom but also dignity—a hope at the heart of democratic life.

Stanley Johnson is a author, recording artist, and contributing editor at Brotha Magazine.