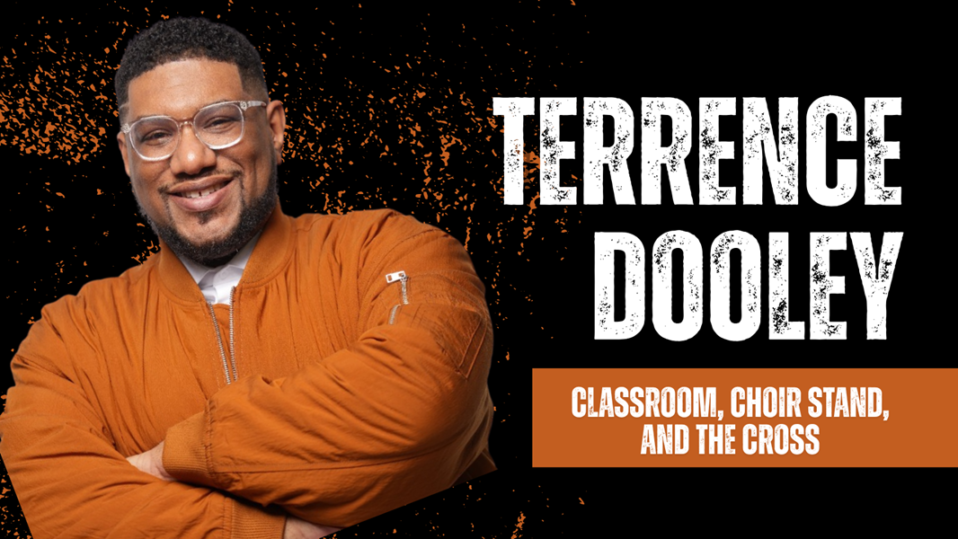

How do I be Black? And American? And Christian?

How does one simultaneously function as all three identities?

The answers to these questions, according to minister, author, father, husband, and student Dante’ Stewart, are complex, perhaps even unfindable. However, to find an answer, he invokes a story by late science fiction novelist Octavia Butler, where a student of her asked if the world she portrayed in her novels Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents mirrored ours.

In other words, was our world as messed up as she made it seem?

The student expected an answer from his Butler as his teacher and Butler, according to Stewart, said, “There is no answer — at least not a singular one. But there are multitudes of answers, and you can become one of yours, if you choose to be.”

Becoming an answer means wrestling between being having the citizenship of being Black in America, and being Black and Christian in the church, and these experiences themselves present conflict for the Black American.

There are no answers, or at least ones easy to find.

“I’m not a magician,” he said. “I can’t conjure answers out of a genie hat. But what I do have is my life and my memories… my traumas and my trials… my testimony and my courage to say there is no single answer.

“But, if you sit a little bit with me, then maybe, we’ll get closer to the future that we so desire for ourselves and one another.”

Stewart has had to answer the question himself – how to concurrently exist as a Black, American, and Christian man – throughout his life experiences, growing up in “the corridor of shame” in rural Lewis, South Carolina to the Memorial Stadium football field of Clemson University.

There, the paradox of being hyper visible as a Black athlete, but invisible as a Black, Christian man who advocated for racial reconciliation and unity, occurred.

“But when you[‘re] just in the everyday thing, everyday movements of this kind of worship experience, we are invisible. We’re caught up in this reality that says, to be in this space is to be Christian first, and then your racial identity is less than or [it] matters second.”

Still, he strived for acceptance. As an athlete, he said, he lived for the phrases “good job,” and “I’m proud of you,” because we learn “whatever we are, and whatever we bring to this world can be taken away from us.”

“And that our worth is dependent on our production for other people. And so, what tends to happen is, when we perform that way, we, in so many ways, give people (and I would even say White people) what they never deserved: trust with our humanity, and trust with our future.”

In looking for that praise from others, and in the process of growing into what he would become – being his own person without giving people the seat of his identity and his humanity — Stewart said he became “terrible” to himself, his teammates, his wife, other Black people and those in the White evangelical space.”

He added, “Oftentimes, we Black men get older, and never figure out or see ourselves and [learn] to embrace our bodies, embrace our beauty, embrace our brilliance to say, ‘I am enough’.”

In addition to answering the question of coexisting as a Black, American, Christian man and personal identity, Stewart, in his book, Shoutin’ in the Fire: An American Epistle, speaks about the importance of masculinity in the educational setting and the church. It is a topic of which he said he is proud, especially the line he wrote that says, “We have been so used to seeing dead Black bodies in the streets, that we often miss living Black bodies, in the shadows.”

“Oftentimes, we see the public execution, either by vigilantes…officers in the eyes of the law…the courts, or even by ourselves and violence. But oftentimes, we don’t see the pain of those who are suffering in private [with] the pain.

Suffering in private can include being performative in front of White evangelicals and not having to deal with the reality of being Black in America. Stewart gave an example where he, as a pastor, could serve and be invisible in the sense of not dealing with the police shooting deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile from the pulpit.

“But I really got to deal with [former President] Donald Trump,” he said, “and the ways in which White people inside of the community to which I call home are not just simply apathetic toward our lives and our death, but they’re hostile toward our suffering and our pain.”

“And so many of us perform and are still invisible and still have to deal with that pain is so alluring, because it works. I could have wr[itten] a book, Shoutin’ in the Fire…that only reduced our lives to the type of lessons that White people could learn and wrote it as Toni Morrison would say, toward the White gaze just to be like, ‘here’s just simply what White people do and what y’all can learn’.”

Instead, while he deemed it more lucrative to do the former, Stewart said the deaths of Sterling and Castile acted as a catalyst for him to not write the type of literature where he was invisible, silent, and performing for other people, especially White people. It was “something he could no longer accept.”

Also catalytic for his writing was the election of Trump in 2016. He described his church’s White congregants as mostly Trump supporters, and he noticed a shift in the conversation where things they supported were essentially weaponizing Christianity against minorities, the LGBTQ+ community, the young, immigrants, and the poor. This enraged him.

“I was angry. It took my wife and one of my friends [to seriously challenge] my own sense of self and identity [and it] broke me down in some legitimate ways,” said Stewart. “That allowed me to sit long enough to ask the question, ‘What did I become?’ And out of that, that’s when I became enraged, where White apathy and hostility started to get the best of me, and I knew I needed something different.”

Dealing with that anger meant seeing himself though different lenses, including how other people, and his wife, saw and challenged him. He also said he had to adjust his perspective of the world. He did so through reading James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, which he said became like the Bible to him, and work by Toni Morrison.

“And I started to realize that they would preach in the same message that Jesus was preaching,” said Stewart, “that the enemy came to steal, kill and destroy. But I came that you may have life and life to the full, and I could not have life in a space that did not see my life or did not see other people’s lives. And I could not receive and uphold a theology that stole from us, that destroy our knowledge production, that devalued us, that did not give us life. And I had to find new ways of thinking and living in the world.”

Along with the texts, his journey led him back to the Black church. Afterward, he took notice of the ways in which Black people were alive in the world, and through that, plus by “leaning on the ancestors,” he gained the courage to self-examine, compassion with himself, and commitment to imagine what he had become.

This article is from an interview with our Editor in Chief Charles Clark.

Article Written by author/educator Brian Thompson who lives in Atlanta, GA with his wife and young son.